Egyptian Hieroglyphs

Definition

The Egyptian hieroglyphic script was one of the writing systems used by ancient Egyptians to represent their language. Because of their pictorial elegance, Herodotus and other important Greeks believed that Egyptian Hieroglyphs were something sacred, so they referred to them as 'holy writing'. Thus, the word hieroglyph comes from the Greek hiero 'holy' and glypho 'writing'. In the ancient Egyptian language, hieroglyphs were called medu netjer, 'the gods' words' as it was believed that writing was an invention of the gods.

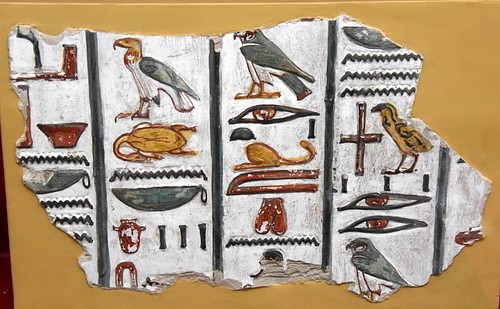

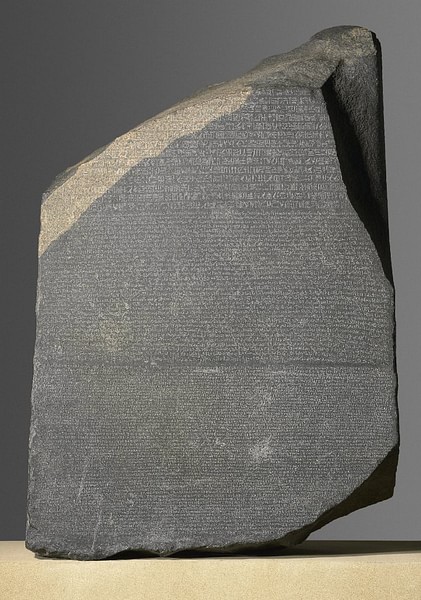

The script was composed of three basic types of signs: logograms, representing words; phonograms, representing sounds; and determinatives, placed at the end of the word to help clarify its meaning. As a result, the number of signs used by the Egyptians was much higher compared to alphabetical systems, with over a thousand different hieroglyphs in use initially and later reduced to about 750 during the Middle Kingdom (2055-1650 BCE). In the 1820s CE, Frenchman Jean-François Champollion famously deciphered hieroglyphs using the 2nd century BCE Rosetta Stone with its triple text of Hieroglyphic, Demotic and Greek. Egyptian hieroglyphs are read either in columns from top to bottom or in rows from the right or from the left.

Origin of Egyptian Hieroglyphs

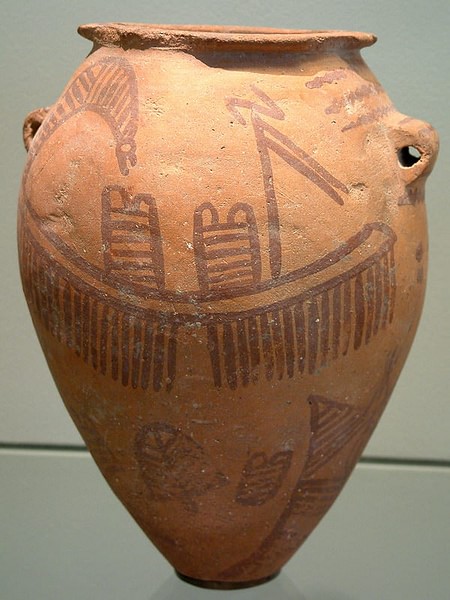

Like most ancient scripts, the origin of Egyptian hieroglyphs is poorly understood. There are, however, several hypotheses that have been put forth. One of the most convincing views claims that they derive from rock pictures produced by prehistoric hunting communities living in the desert west of the Nile, who were apparently familiar with the concept of communicating by means of visual imagery. Some of the motifs depicted on these rock images are also found on pottery vessels of early Pre-dynastic cultures in Egypt. This is especially marked during the Naqada II period (c. 3500-3200 BCE). The vessels were buried in tombs, and it is also in tombs of the Naqada III/Dynasty 0 period (c. 3200-3000 BCE) that the earliest securely dated examples of Egyptian hieroglyphs have been found.

In Abydos' cemetery U, tomb j, a member of the local elite was buried around 3100 BCE. He was a wealthy man, probably a ruler, and he was buried with several goods, including hundreds of jars, an ivory sceptre and other items. Many of these objects were looted and we know about them due to the approximately 150 surviving labels, which contain the earliest known writing in Egypt.

Material Form & Use of Egyptian Hieroglyphs

The labels found in the Abydos U-j tomb were carved on small rectangles made of wood or ivory with a hole in their corner so they could be attached to different goods. Other inscribed surfaces such as ceramic, metal and stone (both flakes and stelae) are also known from early royal tombs.

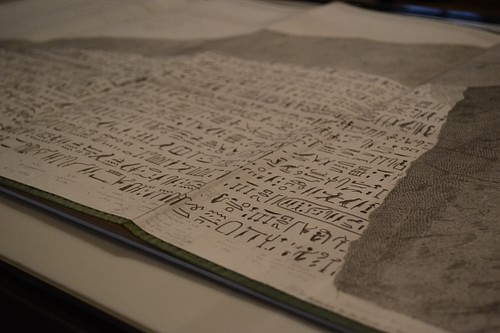

Papyrus, the chief portable writing medium in Egypt, appears during the First dynasty (c. 3000-2890 BCE): the earliest surviving example we know of comes from a blank roll found in the Tomb of Hemaka, an official of King Den. Egyptian scribes used papyrus and other alternative writing surfaces, including writing boards generally made of wood. Until the end of the Eighteenth dynasty (1550-1295 BCE), these boards were covered with a layer of white plaster which could be washed and replastered, providing a convenient reusable surface. Examples of clay tablets, a popular medium in Mesopotamia, dating to the late Old Kingdom (2686-2160 BCE) were found in the Dakhla Oasis, an area far away from the various locations where papyrus was produced. Bone, metal and leather were other type of materials used for writing. Surviving inscriptions on leather dating back to the New Kingdom (1550-1069 BCE) have also been found, but the preservation of leather is poor compared to papyrus, so there is no certainty about how extensively leather was used.

The inscriptions found at Abydos display different types of information: some of them are numbers, others are believed to indicate the origin of the goods, and the most complex show administrative information related to economic activities controlled by the ruler. In tombs from Dynasty 0, the signs found on pottery and stone vessels (and also on the labels attached to them) were used to indicate ownership of their content, probably connected with taxation and other accounting data. The signs on pottery vessels become increasingly standardized and since these pot-marks are believed to express information about the contents of the vessels (including their provenance), this tendency may reflect a growth in the complexity of record keeping and administrative control.

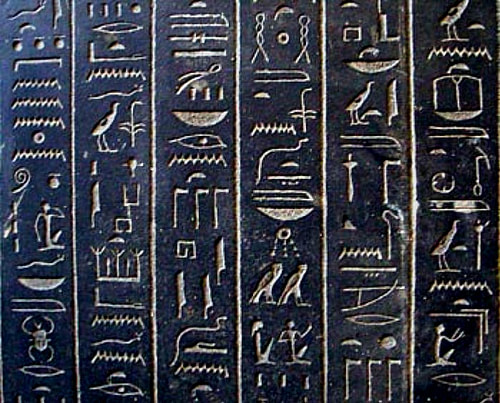

Towards the Late Pre-dynastic/Early dynastic transition (c. 3000 BCE), we find examples of writing in the context of royal art to commemorate royal achievements. In this case, writing is found on ceremonial maceheads, funerary stone stelae and votive palettes: the function of these items was to honour the memory of the rulers both in terms of the ruler's achievements during their life and his relationship with the various gods and goddesses. Around 2500 BCE we find the oldest known examples of Egyptian literature, the “Pyramid Texts”, engraved on pyramids' walls, and later, around 2000 BCE, there emerged a new type of text known as the Coffin Texts, a set of magical and liturgical spells inscribed on coffins.

Development of Ancient Hieroglyphs

As Egyptian writing evolved during its long history, different versions of the Egyptian hieroglyphic script were developed. In addition to the traditional hieroglyphs, there were also two cursive equivalents: hieratic and demotic.

Hieroglyphic

This was the oldest version of the script, characterized by its elegant pictorial appearance. These signs are typically founnd in monument inscriptions and funerary contexts.

Hieratic

Encouraged by priests and temple scribes who wanted to simplify the process of writing, hieroglyphs became gradually stylized and derived into the hieratic 'priestly' script. It is believed that hieratic was invented and developed more or less simultaneously with the hieroglyphic script. Some of the hieroglyphs found in tombs dated to the c. 3200-3000 BCE period were in the form of royal serekhs, a stylized format of the king's name. Some serekhs written on pottery vessels had hieroglyphs in cursive format, possibly a premature stage of hieratic. Hieratic was always written from right to left, mostly on ostraca (pottery sherds) and papyrus, and it was used not only for religious purposes, but also for public, commercial and private documents.

Demotic

An even more abbreviated script lacking any pictorial trace known as demotic 'popular' came in use around the 7th century BCE. The Egyptians called it sekh shat, "writing for documents". With the exception of religious and funerary inscriptions, demotic gradually replaced hieratic. While hieratic still carries some traces of the pictorial hieroglyphic appearance, demotic has no pictorial trace and it is difficult to link demotic signs with its equivalent hieroglyph.

Legends on the Origin of Egyptian Hieroglyphs

According to Egyptian tradition, the god Thoth created writing to make the Egyptians wiser and to strengthen their memory. The god Re, however, disagreed: he said that delivering the hieroglyphs to humanity would cause them to contemplate their memory and history through written documents rather than relying on their actual memories passed down through generations. Writing, in Re's view, would weaken people's memory and wisdom. Despite the will of Re, Thoth gave the techniques of writing to a select number of Egyptians, the scribes. In ancient Egypt, scribes were highly respected for their knowledge and skill in using this gift of the gods and this position was a vehicle of upward social mobility.

Deciphering Hieroglyphs

For many years hieroglyphs were not understood at all. In 1798 CE Napoleon Bonaparte went to Egypt with many researchers and they copied several Egyptian texts and images. One year later, the Rosetta Stone was found, a decree of Ptolemy V, with the same text written in Greek, demotic and hieroglyphic writing.

Finally, Jean-François Champollion unravelled the mystery. He identified the name of Ptolemy V written on the Rosetta Stone, by comparing the hieroglyphs with the Greek translation. Then, he continued to study the names, using an obelisk from Philae (now in Dorset, England). The obelisk had the name of Ptolemy and Cleopatra written on it. This made it possible to conclude that the ancient Egyptian hieroglyphic writing was a mixture of signals representing sounds, ideas and words, not a common alphabet. Champollion's achievement in deciphering the Rosetta Stone unlocked the secret of the ancient Egyptian writing system and allowed the world to finally read into Egyptian history.

Decline of Egyptian Hieroglyphs

During the Ptolemaic (332-30 BCE) and the Roman Period (30 BCE-395 CE) in Egypt, Greek and Roman culture became increasingly influential. Towards the 2nd century CE, Christianity started to displace some of the traditional Egyptian cults. Christianized Egyptians developed the Coptic alphabet (an offshoot of the Greek uncial alphabet), the final stage in the development of the Egyptian language, employed to represent their language.

Examples of the full 32-letter Coptic alphabet are recorded as early as the 2nd century CE. Its use not only reflects the expansion of Christianity in Egypt but it also represents a major cultural breakup: Coptic was the first alphabetic script used in the Egyptian language. Eventually, Egyptian hieroglyphs were replaced by the Coptic script. Only a few signs from the demotic script survived in the Coptic alphabet. The written language of the old gods plunged into oblivion for nearly two millennia, until Champollion's great discovery.