La Transfiguration (Raphaël)

| Artiste | Raphaël |

|---|---|

| Date | 1518-1520 |

| Commanditaire | |

| Type | Huile sur bois |

| Dimensions (H × L) | 405 × 278 cm |

| Mouvements | |

| Collection | |

| Localisation | Musées du Vatican |

La Transfiguration est le dernier tableau peint par Raphaël, commencé en 1518, inachevé de sa main en 1520, date de sa mort. Il est conservé dans la Pinacothèque de la cité du Vatican.

Éléments historiques

La Transfiguration a été commandée à Raphaël par le cardinal Jules de Médicis (futur pape Clément VII). Il commanda en même temps une deuxième œuvre intitulée La résurrection de Lazare à Sebastiano del Piombo. Les deux tableaux d’autel étaient destinés à sa résidence épiscopale de Narbonne, dont il était l‘archevêque depuis 1515. Raphaël mourut d'un accès de fièvre en . Mais il n'a pas le temps d‘achever le tableau. C‘est donc son atelier (probablement Giulio Romano) qui s‘en chargea. Le cardinal Jules de Médicis fit finalement don du tableau à l'église San Pietro in Montorio de Rome où il resta exposé de 1523 à 1797. Le Pape Pie VI fut contraint de le céder à la France en 1797 par le traité de Tolentino (le traité, imposé au Saint-Siège par le Directoire français, consistait, entre autres à prélever cent œuvres parmi les collections pontificales et romaines). Il rejoignit alors le Museum Central des Arts, l’actuel Musée du Louvre, puis fut restitué au Pape Pie VII à la chute de Napoléon et suite aux décisions du Congrès de Vienne, en 1815, imposées à la France. En 1817, le fameux tableau fit retour au Saint-Siège et intégra la Pinacothèque vaticane en 1820.

Composition

Le tableau comporte deux parties narratives distinctes.

La partie supérieure montre la Transfiguration sur le mont Thabor, le Christ flottant devant des nuages illuminés, entre les prophètes Moïse et Élie. En dessous, sur le sommet de la montagne, sont couchés les Apôtres S. Pierre, S. Jacques le Majeur et S. Jean Évangéliste, couvrant leur visage, aveuglés par la lumière.

La partie inférieure montre les autres parmi les Douze Apôtres à qui une foule de gens, paniqués, ont amené un jeune garçon victime d'une possession démoniaque et qu'ils ne parviennent pas à guérir. Le Christ, redescendant du mont Thabor où venait d'avoir lieu sa Transfiguration, guérira l'enfant démoniaque d'une seule parole (cf. Matthieu 17, 14-21)1.

Analyse et iconographie

La Transfiguration est un épisode de la vie du Christ où son apparence physique change pendant sa vie sur terre, révélant ainsi sa nature divine. Selon la Bible, cet épisode se situe après la multiplication des pains, au moment où les disciples reconnaissent en lui le Messie. Au cours de la fête des tentes, il se serait rendu sur le mont Thabor avec ses disciples Pierre, Jacques et Jean et se serait alors métamorphosé. Son visage changea et ses vêtements devinrent d’un blanc éclatant en présence de Moïse et Élie, à droite, reconnaissable aux tables de la loi qu’il tient entre les bras.

On observe une vive lumière blanche l’entourant, provoquant même un vent improbable, surnaturel, traduit par les drapés d’Élie et de Moïse ainsi que leurs cheveux. Les nuages même sont concentrés autour de Jésus. Celui-ci, vêtu de blanc, en léger contrapposto, les hanches larges, le drapé flottant, les bras ouverts, est représenté en lévitation.

Les deux petits personnages, à gauche, qui sont en train de prier et qui n’apparaissent pas dans le passage de la Bible sont les saints Just et Pasteur, à qui est dédiée la cathédrale de Narbonne, dont le commanditaire du tableau, le cardinal Jules de Médicis (futur pape Clément VII) était l'archevêque.

Le mont Thabor est représenté par un monticule. En guise de décor, on peut observer quelques arbres et sur la droite, au lointain, un village.

Cette scène agitée de la partie inférieure du tableau fait référence au passage de l'Évangile de Matthieu, ch. 17, versets 14-21, relatant le cas du garçon possédé, que le Christ, en redescendant du mont Thabor, allait guérir d'une parole.

Si le moment de la scène de la partie supérieure paraît mystérieux et hiératique, les nombreux personnages dans la partie inférieure créent un contraste violent, avec un ensemble de gens pris de panique autour du jeune garçon possédé, se démenant, et de son père, vêtu de vert, qui le retient des deux mains. L'enfant, la bouche ouverte, gesticule, un bras pointé vers le ciel, l'autre vers le sol, les yeux révulsés et exorbités.

À gauche, le groupe des apôtres que le Christ n'a pas pris avec lui sur la montagne (sauf Pierre, Jacques le Majeur et Jean, témoins de la Transfiguration) se consultent sans parvenir à guérir l’enfant. Ils sont également dans la stupeur, sentiment qui se traduit par leurs gestes et leurs regards, dans l'attente du retour du Christ du mont Thabor.

L'usage des couleurs vives (luminisme), les mimiques excessives, annoncent l'école du maniérisme qui dominera bientôt la peinture italienne, après la mort de Raphaël en 1520. Le tableau, l'ultime du maître, reste l'un de ses chefs-d'œuvre les plus marquants.

Bibliographie et Sources

- Nietzsche, Die Geburt der Tragödie aus dem Geist der Musik

- Giorgio Vasari, dans Le Vite qui qualifie le tableau de « ... le plus célèbre, le plus beau et le plus divin. » (« fra tante quante egli ne fece, sia la piú celebrata, la piú bella e la piú divin »).

- Notice des tableaux exposés dans la galerie Napoléon, (lire en ligne [archive]), p. 1152. La Transfiguration : « Jules de Médicis, archevêque de Narbonne, (...) ordonna le tableau pour sa cathédrale. La mort de Raphaël changea cette destination. C'est à la Victoire, que la France doit ce chef-d’œuvre qui lui était destiné. »

- Stendhal, au Chapitre I de Vie de Henry Brulard, évoque ce tableau: « Je me trouvais ce matin, , à San Pietro in Montorio, sur le mont Janicule, à Rome il faisait un soleil magnifique. [...] C'est donc ici que la Transfiguration de Raphaël a été admirée pendant deux siècles et demi. Quelle différence avec la triste galerie de marbre gris où elle est enterrée aujourd'hui au fond du Vatican ! Ainsi pendant deux cent cinquante ans ce chef-d'œuvre a été ici, deux cent cinquante ans !... »

- Gregor Bernhart-Königstein: Raffaels Weltverklärung: Das berühmteste Gemälde der Welt. Petersberg: Imhof 2007.

- ===============================================================

Raffaello Sanzio, The Transfiguration

Transfiguration (Raphael)

| The Transfiguration | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Raphael |

| Year | 1516–20 |

| Medium | Tempera on wood |

| Dimensions | 405 cm × 278 cm (159 in × 109 in) |

| Location | Pinacoteca Vaticana, Vatican City |

The Transfiguration is the last painting by the Italian High Renaissance master Raphael. Commissioned by Cardinal Giulio de Medici, the later Pope Clement VII (1523–1534), and conceived as an altarpiece for the Narbonne Cathedral in France, Raphael worked on it until his death in 1520. The painting exemplifies Raphael's development as an artist and the culmination of his career. Unusually for a depiction of the Transfiguration of Jesus in Christian art, the subject is combined with the next episode from the Gospels (the healing of a possessed boy) in the lower part of the painting. The Transfiguration stands as an allegory of the transformative nature of representation.[1] It is now in the Pinacoteca Vaticana in Vatican City.

From the late 16th century until the early 20th century, it was said to be the most famous oil painting in the world.

By December 1516, the latest date of commission, Cardinal Giulio de Medici, cousin to Pope Leo X (1513–1521), was also the Pope's vice-chancellor and chief advisor. He had been endowed with the legation of Bologna, the bishoprics of Albi, Ascoli, Worcester, Eger and others. From February 1515, this included the archbishopric of Narbonne.[2] He commissioned two paintings for the cathedral of Narbonne, The Transfiguration of Christ from Raphael and The Raising of Lazarus from Sebastiano del Piombo. With Michelangelo providing drawings for the latter work, Medici was rekindling the rivalry initiated a decade earlier between Michelangelo and Raphael, in the Stanze and Sistine Chapel.[3]

From 11 to 12 December 1516, Michelangelo was in Rome to discuss with Pope Leo X and Cardinal Medici the facade of the Basilica of San Lorenzo in Florence. During this meeting, he was confronted with the commission of The Raising of Lazarus and it was here that he agreed to provide drawings for the endeavour, but not to execute the painting himself. The commission went to Michelangelo's friend Sebastiano del Piombo. As of this meeting the paintings would become emblematic of a paragone between two approaches to painting, and between painting and sculpture in Italian art.[2]

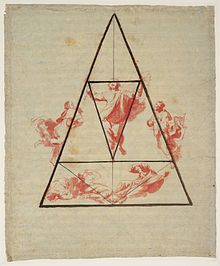

An early modello for the painting, done in Raphael's studio by Giulio Romano, depicted a 1:10 scale drawing for The Transfiguration. Here Christ is shown on Mount Tabor. Moses and Eljah float towards him; John and James are kneeling to the right; Peter is to the left. The top of the model depicts God the Father and a throng of angels.[2] A second modello, done by Gianfrancesco Penni, shows a design with two scenes, as the painting was to develop. This modello is held by the Louvre.[4]

The Raising of Lazarus was unofficially on view by October 1518. By this time Raphael had barely started on his altarpiece. By the time Sebastiano del Piombo's work was officially inspected in the Vatican by Leo X on Sunday, 11 December 1519, the third Sunday of Advent, The Transfiguration was still unfinished.[2]

Raphael would have been familiar with the final form of The Raising of Lazarus as early as the autumn of 1518, and there is considerable evidence that he worked feverishly to compete, adding a second theme and nineteen figures.[2] A surviving modello for the project, now in the Louvre (a workshop copy of a lost drawing by Raphael's assistant Gianfrancesco Penni) shows the dramatic change in the intended work.

Examination of the final Transfiguration revealed more than sixteen incomplete areas and pentimenti (alterations).[2] An important theory holds that the writings of Blessed Amadeo Menes da Silva was key to the transformation. Amadeo was an influential friar, healer and visionary as well as the Pope's confessor. He was also diplomat for the Vatican State. In 1502, after his death, many of Amadeo's writings and sermons were compiled as the Apocalypsis Nova. This tract was well known to Pope Leo X. Guillaume Briçonnet, Cardinal Giulio de' Medici's predecessor as bishop of Narbonne, and his two sons also consulted the tract as spiritual guide. Cardinal Giulio knew the Apocalypsis Nova and could have influenced the painting's final composition. Amadeo's tract describes the episodes of the Transfiguration and the possessed boy consecutively. The Transfiguration represents a prefiguration of the Last Judgment, and of the final defeat of the Devil. Another interpretation is that the epileptic boy has been cured, thus linking the divinity of Christ with his healing power.[5]

Raphael died on 6 April 1520. For a couple of days afterward, The Transfiguration lay at the head of his catafalque at his house in the Borgo.[6][7] A week after his death, the two paintings were exhibited together in the Vatican.[2]

While there is some speculation that Raphael's pupil, Giulio Romano, and assistant, Gianfrancesco Penni, painted some of the background figures in the lower right half of the painting,[3] there is no evidence that anyone but Raphael finished the substance of the painting.[2] The cleaning of the painting from 1972 to 1976 revealed that assistants only finished some of the lower left figures, while the rest of the painting is by Raphael himself.[1]

Rather than send it to France, Cardinal Giulio de' Medici retained the picture. In 1523,[4] he installed it on the high altar in the Blessed Amadeo's church of San Pietro in Montorio, Rome,[8] in a frame which was the work of Giovanni Barile (no longer in existence). A mosaic copy of the painting was completed by Stefano Pozzi in St. Peter's Basilica in the Vatican City in 1774.[4]

In 1797, during Napoleon Bonaparte's Italian campaign, it was taken to Paris by French troops and installed in the Louvre. Already on 17 June 1794, Napoleon's Committee of Public Instruction had suggested an expert committee accompany the armies to remove important works of art and science for return to Paris. The Louvre, which had been opened to the public in 1793, was a clear destination for the art. On 19 February 1799, Napoleon concluded the Treaty of Tolentino with Pope Pius VI, in which was formalized the confiscation of 100 artistic treasures from the Vatican.[9]

Among the most sought after treasures Napoleons agents coveted were the works of Raphael. Jean-Baptiste Wicar, a member of Napoleon's selection committee, was a collector of Raphael's drawings. Baron Antoine-Jean Gros, another member, had been influenced by Raphael. For artists like Jacques-Louis David, and his pupils Girodet and Ingres, Raphael represented the embodiment of French artistic ideals. Consequently, Napoleon's committee seized every available Raphael. To Napoleon, Raphael was simply the greatest of Italian artists and The Transfiguration his greatest work. The painting, along with the Apollo Belvedere, the Laocoön, the Capitoline Brutus and many others, received a triumphal entry into Paris on 27 July 1798, the fourth anniversary of Maximilien de Robespierre's fall.[9]

In November 1798, The Transfiguration was on public display in the Grand Salon at the Louvre. As of 4 July 1801, it became the centrepiece of a large Raphael exhibition in the Grande Galerie. More than 20 Raphaels were on display. In 1810, a famous drawing by Benjamin Zix recorded the occasion of Napoleon and Marie Louise's wedding procession through the Grande Galerie, The Transfiguration on display in the background.[9]

The painting's presence at the Louvre gave English painters like Joseph Farington (on 1 and 6 September 1802)[10]:1820–32 and Joseph Mallord William Turner (in September 1802) the opportunity to study it. Turner would dedicate the first of his lectures as Professor of Perspective at the Royal Academy to the picture.[11] Farington also reported on others having been to see the picture: Swiss painter Henry Fuseli, for whom it was second at the Louvre only to Titian's The Death of St. Peter Martyr (1530), and English painter John Hoppner.[10]:1847 The Anglo-American painter Benjamin West "said that the opinion of ages stood confirmed that it still held the first place".[10]:1852 Farington himself expressed his sentiments as follows:

After the fall of Napoleon Bonaparte, in 1815, envoys to Pope Pius VII, Antonio Canova and Marino Marini managed to secure The Transfiguration (along with 66 other pictures) as part of the Treaty of Paris. By agreement with the Congress of Vienna, the works were to be exhibited to the public. The original gallery was in the Borgia Apartment in the Apostolic Palace. After several moves within the Vatican, the painting now resides in the Pinacoteca Vaticana.[12]

Reception[edit]

The reception of the painting is well documented. Between the year 1525 and 1935, at least 229 written sources can be identified that describe, analyse, praise or criticise The Transfiguration.[13]

The first descriptions of the painting after Raphael's death in 1520 called The Transfiguration already a masterpiece, but this status evolved until the end of the 16th century. In his notes of a travel to Rome in 1577, the Spanish humanist Pablo de Céspedes called it the most famous oil-painting in the world for the first time.[14] The painting would preserve this authority for more than 300 years. It was acknowledged and repeated by many authors, like the connoisseur François Raguenet, who analysed Raphael's composition in 1701. In his opinion, its outline drawing, the effect of light, the colours and the arrangement of the figures made The Transfiguration the most perfect painting in the world.[15]

Jonathan Richardson Senior and Junior dared to criticise the overwhelming status of The Transfiguration, asking if this painting could really be the most famous painting in the world.[16] They criticised that the composition was divided into an upper and a lower half that would not correspond to each other. Also the lower half would draw too much attention instead of the upper half, while the full attention of the viewer should be paid to the figure of Christ alone. This criticism did not diminish the fame of the painting, but provoked counter-criticism by other connoisseurs and scholars. For the German-speaking world, it was the assessment by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe that prevailed. He interpreted the upper and the lower half as complementary parts. This assessment was quoted by many authors and scholars during the 19th century and thus the authority of Goethe helped to save the fame of The Transfiguration.[17]

During the short period of time the painting spent in Paris, it became a major attraction to visitors, and this continued after its return to Rome, then placed in the Vatican museums. Mark Twain was one of many visitors and he wrote in 1869: "I shall remember The Transfiguration partly because it was placed in a room almost by itself; partly because it is acknowledged by all to be the first oil painting in the world; and partly because it was wonderfully beautiful."[18]

In the early 20th century, the fame of the painting rapidly diminished and soon The Transfiguration lost its denomination as the most famous painting in the world. A new generation of artists did not accept Raphael as an artistic authority anymore. Copies and reproductions were no longer in high demand. While the complexity of the composition had been an argument to praise the painting until the end of the 19th century, viewers were now repelled by it. The painting was felt to be too crowded, the figures to be too dramatic and the whole setting to be too artificial. In contrast, other paintings like the Mona Lisa by Leonardo da Vinci were much easier to recognise and did not suffer from the decline of the overwhelming status of Raphael as an artistic example.[19] Thus The Transfiguration is a good example for the changeability of the fame of an artwork, that may last for centuries but may also decline in just a short period.

Reproductions

The fame of the painting is also based on its reproduction. While the original could only be admired in one place – in Rome, and for a short period of time in Paris after it had been taken away by Napoleon – the large number of reproductions ensured that the composition of the painting was omnipresent in nearly every important art collection in Europe. It could thus be studied and admired by many collectors, connoisseurs, artists and art historians.

Including the mosaic in St Peter’s in the Vatican, at least 68 copies were made between 1523 and 1913.[13] Good copies after the painting were highly sought after during the Early Modern period and young artists could earn money for an Italian journey by selling copies of The Transfiguration. One of the best painted copies ever was made by Gregor Urquhart in 1827.[20] At least 52 engravings and etchings were produced after the painting until the end of the 19th century, including illustrations for books like biographies and even for Christian songbooks.[13] The Istituto nazionale per la grafica in Rome possesses twelve of these reproductions.[21] At least 32 etchings and engravings can be traced that depict details of the painting, sometimes to use them as a part of a new composition.[13] Among these depictions of details is one set of prints of heads, hands and feet engraved by G. Folo after Vincenzo Camuccini (1806), and another set of heads produced in stipple engraving by J. Godby after drawings by I. Goubaud (1818 and 1830). The first engraved reproduction of The Transfiguration is also called to be the first reproductive print of a painting ever. It was made by an anonymous engraver in 1538 and is sometimes identified with the manner of Agostino Veneziano.

Iconography

Raphael's painting depicts two consecutive, but distinct, biblical narratives from the Gospel of Matthew, also related in the Gospel of Mark. In the first, the Transfiguration of Christ itself, Moses and Elijah appear before the transfigured Christ with Peter, James and John looking on (Matthew 17:1–9; Mark 9:2–13). In the second, the Apostles fail to cure a boy from demons and await the return of Christ (Matthew 17:14–21; Mark 9:14).[3]

The upper register of the painting shows the Transfiguration itself (on Mount Tabor, according to tradition), with the transfigured Christ floating in front of illuminated clouds, between the prophets Moses, on the right, and Elijah, on the left,[22] with whom he is conversing (Matthew 17:3). The two figures kneeling on the left are commonly identified as Justus and Pastor who shared August 6 as a feast day with the Feast of the Transfiguration.[23] These saints were the patrons of Medici's archbishopric and the cathedral for which the painting was intended.[2] It has also been proposed that the figures might represent the martyrs Saint Felicissimus and Saint Agapitus who are commemorated in the missal on the feast of the Transfiguration.[4][23]

The upper register of the painting includes, from left to right, James, Peter and John,[24] traditionally read as symbols of faith, hope and love; hence the symbolic colours of blue-yellow, green and red for their robes.[2]

In the lower register, Raphael depicts the Apostles attempting to free the possessed boy of his demonic possession. They are unable to cure the sick child until the arrival of the recently transfigured Christ, who performs a miracle. The youth is no longer prostrate from his seizure but is standing on his feet, and his mouth is open, which signals the departure of the demonic spirit. As his last work before this death, Raphael (which in Hebrew רָפָאֵל [Rafa'el] means "God has healed"), joins the two scenes together as his final testament to the healing power of the transfigured Christ. According to Goethe: "The two are one: below suffering, need, above, effective power, succour. Each bearing on the other, both interacting with one another."[25]

The man lower left is the apostle-evangelist Matthew, some would says St. Andrew,[4] depicted at eye-level and serving as interlocutor with the viewer.[2] The function of figures like the bottom left was best described by Leon Battista Alberti almost a century earlier in 1435.

Matthew (or Andrew) gestures to the viewer to wait, his gaze focused on a kneeling woman in the lower foreground. She is ostensibly a part of the family group,[22] but on closer examination is set apart from either group. She is a mirror image of a comparable figure in Raphael's The Expulsion of Heliodorus from the Temple (1512).[3] Giorgio Vasari, Raphael's biographer, describes the woman as "the principal figure in that panel". She kneels in a contrapposto pose, forming a compositional bridge between the family group on the right and the nine apostles on the left. Raphael also renders her in cooler tones and drapes her in sunlit pink, while he renders the other participants, apart from Matthew, oblivious to her presence.[1] The woman's contrapposto pose is more specifically called a figura serpentinata or serpent's pose, in which the shoulders and the hips move in opposition; one of the earliest examples being Leonardo da Vinci's Leda (c. 1504), which Raphael had copied while in Florence.[1]

In the centre are four apostles of different ages. The blonde youth appears to echo the apostle Philip from The Last Supper. The seated older man is Andrew. Simon is the older man behind Andrew. Judas Thaddeus is looking at Simon and pointing towards the boy.[2]

The apostle on the far left is widely considered to be Judas Iscariot[22] He was the subject of one of only six surviving so-called auxiliary cartoons, first described by Oskar Fischel in 1937.[27]

Analysis and interpretation[edit]

The iconography of the picture has been interpreted as a reference to the delivery of the city of Narbonne from the repeated assaults of the Saracens. Pope Calixtus III proclaimed August 6 a feast day on the occasion of the victory of the Christians in 1456.[4]

Enlightenment philosopher Montesquieu noted that the healing of the obsessed boy in the foreground takes precedence over the figure of Christ. Modern critics have furthered Montesquieu's criticism by suggesting that the painting should be renamed to "Healing of the Obsessed Youth".[28]

J. M. W. Turner had seen The Transfiguration in the Louvre, in 1802. At the conclusion of the version of his first lecture, delivered on 7 January 1811, as Professor of Perspective at the Royal Academy, Turner demonstrated how the upper part of the composition is made up of intersecting triangles, forming a pyramid with Christ at the top.[29]

In a 1870 publication, German art historian Car Justi observes that the painting depicts two subsequent episodes in the biblical narrative of Christ: after the transfiguration, Jesus encounters a man who begs mercy for his devil-possessed son.[30]

Raphael plays on a tradition equating epilepsy with the aquatic moon (luna, from whence lunatic). This causal link is played on by the watery reflection of the moon in the lower left corner of the painting; the boy is literally moonstruck.[2] In Raphael's time, epilepsy was often equated with the moon (morbus lunaticus), possession by demons (morbus daemonicus), and also, paradoxically, the sacred (morbus sacer). In the 16th century, it was not uncommon for sufferers of epilepsy to be burned at the stake, such was the fear evoked by the condition.[31] The link between the phase of the moon and epilepsy would only be broken scientifically in 1854 by Jacques-Joseph Moreau de Tours.[32]

Raphael's Transfiguration can be considered a prefiguration of both Mannerism, as evidenced by the stylised, contorted poses of the figures at the bottom of the picture; and of Baroque painting, as evidenced by the dramatic tension imbued within those figures, and the strong use of chiaroscuro throughout.

As a reflection on the artist, Raphael likely viewed The Transfiguration as his triumph.[33] Raphael uses the contrast of Jesus presiding over men to satiate his commissioners in the Roman Catholic Church. Raphael uses the cave to symbolize the Renaissance style, easily observed in the extended index finger as a reference to Michelangelo's Sistine Chapel. Additionally, he subtly incorporates a landscape in the background, but uses darker coloring to show his disdain for the style. Yet the focal point for the viewer is the Baroque styled child and his guarding father. In all, Raphael successfully appeased his commissioners, paid homage to his predecessors, and ushered in the subsequent predominance of Baroque painting.

On the simplest level, the painting can be interpreted as depicting a dichotomy: the redemptive power of Christ, as symbolised by the purity and symmetry of the top half of the painting; contrasted with the flaws of Man, as symbolised by the dark, chaotic scenes in the bottom half of the painting.

The philosopher Nietzsche interpreted the painting in his book The Birth of Tragedy as an image of the interdependence of Apollonian and Dionysian principles.[34]

The sixteenth-century painter and biographer Giorgio Vasari wrote in his Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects that The Transfiguration was Raphael's "most beautiful and most divine" work.

===================================================

Raffaello Sanzio, Transfiguration

Le Cardinal Jules de Médicis commanda deux peintures destinées à la cathédrale Saint-Juste de Narbonne. Le cardinal de Médicis (futur pape Clément VII) était en effet devenu évêque de Narbonne en 1515. La Transfiguration fut confiée à Raphaël et la Résurrection de Lazare (aujourd’hui à la National Gallery de Londres) à Sebastiano del Piombo. La Transfiguration ne fut jamais envoyée en France parce que le cardinal la conserva à la mort de Raphaël (1520) puis il en fit don à l’église Saint-Pierre in Montorio où l’œuvre fut placée sur le maître autel. En 1797, à la suite du Traité de Tolentino, cette œuvre, comme tant d’autres, fut emportée à Paris puis restituée en 1816 à la chute de Napoléon. C’est alors qu’elle entra dans la Pinacothèque de Pie VII (pontificat de 1800 à 1823). Le retable représente deux épisodes racontés l’un après l’autre dans l’Evangile selon saint Matthieu : La Transfiguration en haut, avec le Christ en gloire entre les prophètes Moïse et Elie ; en bas au premier plan, la rencontre des Apôtres avec l’enfant possédé que Jésus guérira à son retour du Mont Thabor. Il s’agit de la dernière œuvre de Raphaël, son testament spirituel. Giorgio Vasari, célèbre artiste et biographe du XVIe siècle, l’a décrite comme « la plus célébrée, la plus belle et la plus divine. »

==========================================================

Where? Room 8 of the Pinacoteca in the Vatican Museums When? 1516-1520 Commissioned by? Archbishop Giulio de’ Medici (who later became Pope Clement VII) for a chapel in the Narbonne Cathedral in Narbonne, France. What do you see? Two unrelated biblical events. On top is the story of the transfiguration of Christ. At the bottom is the story of a young man who is possessed by a demon.

In 1523, the painting was placed in the San Pietro in Montorio Church in Rome. Over the centuries, numerous artists and art experts considered this to be the best painting ever. Biblical stories: The story on top is the transfiguration and on the bottom is The Healing of the Lunatic Boy. Both stories are described in Matthew 17, Mark 9, and Luke 9. The biblical story describes how Jesus is transfigured in radiant glory when praying with three of his disciples on a mountain. Jesus speaks with Moses and Elijah and also hears the voice of God. The Feast of the Transfiguration is still celebrated in many churches, either on August 6 or August 19. The story of the demon-possessed boy occurs at the same time as the transfiguration. When Jesus and his three disciples came down from the mountain, the father of the boy kneels down in front of Jesus and asks him to heal his son as the disciples were unable to do that. In 1605, Peter Paul Rubens painted a variation of the Transfiguration. Symbolism: The transfiguration shows the connection that Jesus provides between Heaven and Earth and that people should follow the lessons provided by the Son of God. To emphasize this, Jesus is looking upwards to the sky to remind us that he provides the connection between the people on earth and God in Heaven. The three disciples on the mountain represent faith, hope, and love. The scene at the bottom half of the painting symbolizes the inability of people to do miracles without the trust in God's abilities. Who is Raphael? Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino (1483-1520) was a very productive painter. Despite his short life, he completed many works. Together with Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo, he is considered to be the most influential painter of his time. The Transfiguration is considered to be one of Raphael's best works, only surpassed according to some by his fresco of the School of Athens, which is also in the Vatican Museums. The Transfiguration was ahead of its time. It contains some elements of both the Mannerism and Baroque style of painting, and it has had a big influence on the development of both styles. With such a masterpiece, it was a pity that Raphael died on Good Friday 1520. The painting of the Transfiguration was exposed next to the body of Raphael in the days after his death, and it was initially placed above his tomb in the Pantheon. Fun fact: The story behind this painting has been debated for centuries as it was not clear why Raphael combined two such different biblical stories in a single painting. There are many explanations, but no consensus. A first explanation is that Raphael was competing with Del Piombo who was commissioned a painting for the same church. After he saw the completed painting of Del Piombo, Raphael decided to add additional figures to the painting to outshine the painting of Del Piombo (a protégé of Michelangelo, Raphael’s biggest rival). A second interpretation is given by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe who wrote that the painting was clearly an integrated piece. At the bottom are the people who are suffering and need the help of Jesus (emphasized by the more chaotic and dark scene) and on the top is the power of Jesus which the people at the bottom need (emphasized by the serene and bright scene). A third interpretation is that Raphael combined these two scenes because of the meaning of his name. Raphael means ‘God heals’ in Hebrew. This would explain that the disciples at the bottom could not heal the young man, but that Jesus, through the power of God, could heal him. You can pick the interpretation that you prefer. Interested in a copy for yourself? Poster or canvas Written by Eelco Kappe References:

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||